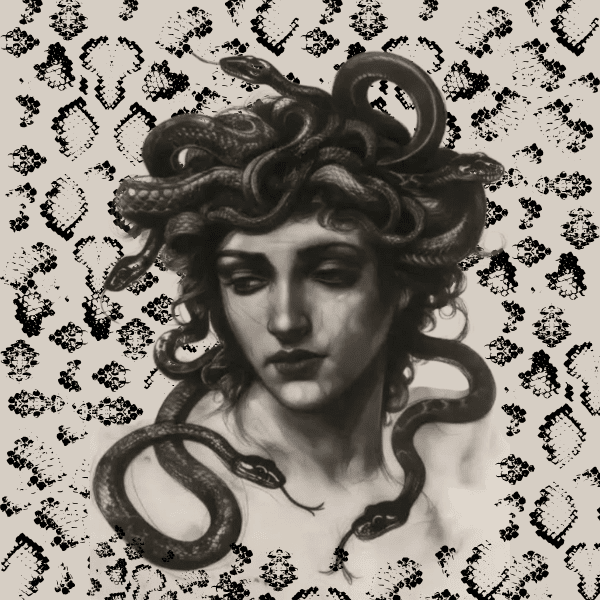

No man or monster has slithered their way into our hearts quite like the snake-haired seductress with the obsidian stare. With a gaze that can turn men to stone, she has been terrorizing and petrifying humanity for thousands of years; Medusa.

The Origin Medusa

Medusa’s history dates back all the way to the works of Homer. Homer writes that the warrior Goddess Athena arms herself with an aegis (a piece of clothing or a shield, it’s not entirely clear) that bears a “Gorgon head.” The Gorgon is a quote “fearful monster, fearful and terrible,” according to Homer in both the Iliad and the Odyssey.

So, what’s a Gorgon? According to Greek mythology the Gorgons were the three daughters of the sea gods Phorcys and Ceto. Greek poet Hesiod described Medusa and her sisters as women with snakes hanging from their belts. Greek scholar Apollodorus, described the Gorgon sisters as having scaled heads, large tusks and golden wings. He also adds one other crucial detail that Medusa loses her head at the hands of Perseus, the half-god offspring of Zeus.

Medusa: Before She Had Fangs

To understand the Medusa mythology story, we need to peel back the centuries like serpent skin. She wasn’t originally a lone figure, but one of three Gorgon sisters—daughters of primordial sea gods, Phorcys and Ceto. While her sisters were immortal, Medusa was famously mortal—and that alone made her vulnerable.

Some of the earliest mentions, like those from Homer and Hesiod, don’t describe a beautiful woman cursed by gods, but a terrifying creature with a scaly head, golden wings, and a tongue that lolled like a hound’s. The medusa mythology origin, then, is not a beauty transformed into horror—but horror from the start. So what changed?

Ovid happened. In his Metamorphoses, Medusa is reimagined: once a stunning woman with glorious hair, she’s raped by Poseidon in Athena’s temple. And Athena, rather than punishing the sea god, punishes Medusa—transforming her hair into snakes and making her eyes fatally powerful. As always, in mythology and history alike, the divine feminine bears the weight of male violence.

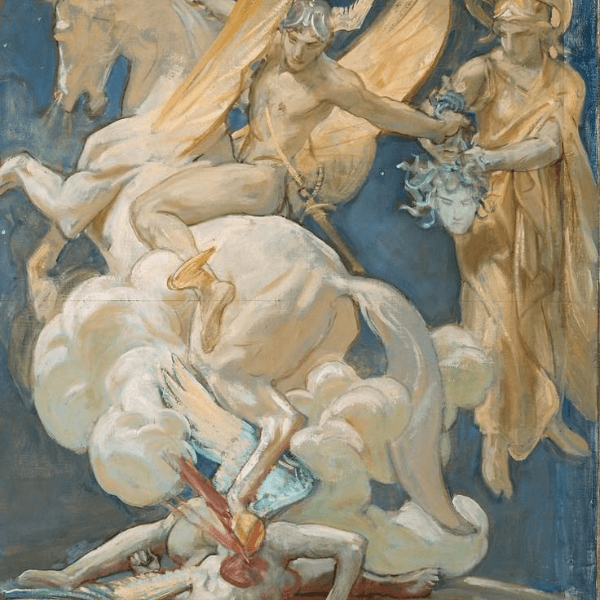

A Severed Head, A Winged Horse

Then comes Perseus. Armed with magical items—including Hades’ helmet of invisibility, Hermes’ winged sandals, and a mirrored shield—he slays the sleeping Medusa without ever looking her in the eyes. Perseus and the Gorgon Medusa become the classic hero vs. monster tale. But here’s where the myth gets poetic: from Medusa’s decapitated body springs Pegasus—a creature of pure freedom—and Chrysaor, a warrior with a golden sword.

From the death of one woman, two symbols of male power are born. Sound familiar?

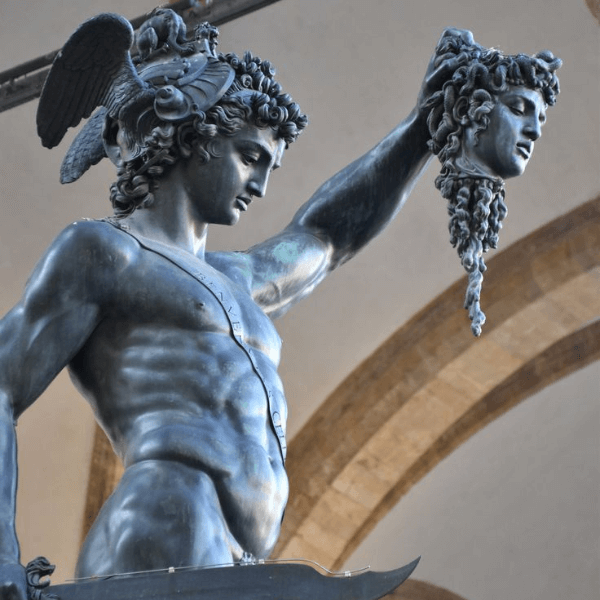

Medusa Symbolism: Protection & Provocation

The irony is sharp enough to cut with: Medusa, once defiled and disfigured, became a symbol of protection. Her severed head was fastened to Athena’s shield, carved into temples and weapons, worn as an amulet to ward off evil. Not because she was loved—but because she was feared. The Gorgon face—the orgon medusa—was not meant to be pretty. It was meant to be terrifying, and thus, powerful.

It wasn’t until much later, through the lens of Renaissance art and psychoanalysis, that her image was twisted again. Once a mythical creature of strength and survival, she became a woman overcome by her own beauty and rage. Her snakes no longer symbols of divine wildness, but shame and punishment.

The Modern Medusa

The first century BC and the Roman poet Ovid decided to reboot the Medusa franchise with his own origin story and things get a lot dramatic for Medusa. In Metamorphoses, She is beautiful with lovely flowing, long hair. One day, the god Neptune finds her in a temple dedicated to Minerva and rapes her. Minerva punishes the outrage by transforming Medusa’s hair into serpents; and with that, the modern Medusa takes shape. She’s got snakes for hair and a deadly eye contact.

There are a few theories on Medusa’s origins and how her story has evolved, but why the strange power to turn men into stone with just a gaze? Its possible that we’ll never be sure what the real reason for this is. However we can find an explanation for why is Medusa female? A female with dramatic serpentine hair, and powerful petrifying gaze.

From A Symbol Of Protection To A Sign Of Seduction

Actually, from the Ancient Greeks to the Middle Ages, she was a sign of protection! Shields and temple doors were adorned with images of her, a face with a protruding tongue, wide eyes, and fangs. She served as a warning. Perhaps it can be said that Medusa is one of the ancient interpretations of the evil eye. It was during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that Medusa moves from terrifying monster to predatory, seductive woman. Through a Christian lens, she was seen as vice incarnate—as a symbol of a woman’s power to lead men astray. Perseus is reframed as a symbol of virtue, triumphing over Medusa. So, a victim of sexual assault becomes a predatory sexual being.

But it’s in the the Century that Medusa, with a little help from poet Percy Shelley, sheds that skin and undergoes her most interesting transformation of all … After seeing this painting, incorrectly attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, Shelley was inspired to write a poem about Medusa. Shelley attributes her power to “grace” not evil, writing:

“Its horror and its beauty are divine.

Upon its lips and eyelids seems to lie

Loveliness like a shadow, from which shine,

Fiery and lurid, struggling underneath,

8 The agonies of anguish and of death.(1)”

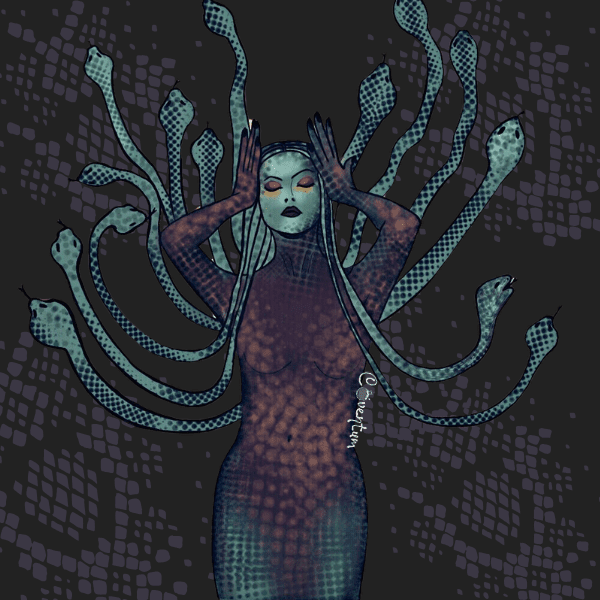

Insıde Medusa’s Psyche

Freud, unsurprisingly, saw her as a metaphor for castration anxiety. (Thanks, Sigmund.) But many modern feminists flipped the lens. Instead of a warning, they saw a mirror. Medusa became the face of feminine rage, of survivors made dangerous by their refusal to be quiet.

She represents the threat of the female gaze in a world built to objectify it. Her eyes don’t seduce—they confront. Her beauty doesn’t invite—it warns. No wonder she had to be destroyed.

Medusa: The Female Hero

With these words Shelley finds something new in the story of Medusa:

“Not a stoney stare, but a mesmerizing gaze. Not a monster, but a terrifying beauty. Not vice incarnate, but the feminine sublime.”

More recently, some feminists adopted Medusa as a symbol of female resistance and revenge. A creature that can literally turn the leering male gaze against itself. But not all interpretations have been so generous. Leave it to Sigmund Freud who argued that the Medusa myth was a metaphor for a fear of castration.

In films like Clash of the Titans and Percy Jackson and the Olympians we see Medusa both as the powerful, dangerous living woman, and as a defeated, decapitated head. Medusa’s gender is her defining feature—just as much as that writhing head of snakes. Remember, it is never just the eyes that are removed to take her power, the whole head is needed—the female face in its entirety. Her defeat by decapitation demonstrates that we see femininity as a threat.

Medusa’s Gaze Still Lingers

You’ll still see her—on shields, on sculptures, on runways. But now, more than ever, we see her through different eyes. As a woman goddess symbol, Medusa teaches that what is feared is often powerful, and what is powerful is often punished.

Her story is not about vanity. It’s about vengeance. Not about beauty. But survival. Not a monster. But a myth turned mirror. So is she a villain or a victim? Maybe she’s both. Maybe that’s the point.

She still lingers in our collective imagination because she’s a powerful symbol. If you think women are scary, Meusa is a scary woman. But if you look a little deeper, you’ll find there’s more than meets the eye.

References:

- Britannica, Medusa | Myth & Story

Psychology Today, The Monsters That Make Us: Things That Go Bump in the Mind

The Guardian, Greek Myths: A New Retelling by Charlotte Higgins; Medusa: The Girl Behind the Myth by Jessie Burton – review

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art

Wikipedia, Medusa’s Head - Psychology Today, The Significance of Hair

Art UK, Rethinking Medusa: the ‘nasty woman’ of mythology - Arcadia, “Off With Her Head!”: Medusa and Feminism

- Medium, From Beauty to Monster: Medusa as a Symbol of Female Rage and Empowerment

[…] Medusa, often depicted as a monster, is now reclaimed as a symbol of resistance against male violence. She […]