Once upon a time, the gods whispered secrets into the ears of mortals, shaping the way they perceived the world. In their stories, heroes stumbled, villains schemed, and fate played its cruel games. But beneath these grand tales lay something deeper—lessons on human nature, cognition, and the ways our own minds can deceive us. What if mythology wasn’t just a collection of ancient fables but a guidebook for understanding our own flawed thinking?

Mythology and Humanity

Friedrich Nietzsche, ever the poetic philosopher, looked at Greek mythology and saw a map of the human condition. He spoke of two opposing yet intertwined forces: Apollonian order and Dionysian chaos. The Apollonian is the structured, rational side—the god of light, form, and reason. Dionysus, on the other hand, is the wild, instinctual force of passion, creativity, and destruction. Life, according to Nietzsche, is an eternal dance between these two extremes. Too much order stifles the soul, too much chaos engulfs it. Balance is key.

Carl Jung took this further, introducing the concept of archetypes—universal symbols and characters embedded in the human psyche. Gods, heroes, and monsters weren’t just mythological figures; they were reflections of the mind itself. By understanding these archetypes, Jung believed we could navigate our inner landscapes and better understand our subconscious drives.

Now, let’s take a Nietzschean-Jungian approach to modern thinking errors—also known as cognitive distortions—through the lens of mythology.

The Achilles’ Heel: Overgeneralization

One failure, one mistake, and suddenly we believe it defines our entire existence. We slip up at work and think, I’m completely incompetent. We get rejected once and decide, I’ll always be alone.

Achilles, the nearly invincible warrior, had only one weakness—his heel. Imagine if he had focused solely on this flaw, believing himself to be entirely vulnerable, despite his overwhelming strength. He could not even go out on the battlefield because of fear, constantly thinking about his heel. This is overgeneralization in action: allowing a single flaw to overshadow everything else.

Pandora’s Box: Black-and-White Thinking

The world isn’t just good or bad, right or wrong, success or failure. Yet, when trapped in black-and-white thinking, we discard nuance and embrace extremes.

Pandora, driven by curiosity, opened a forbidden box and unleashed chaos upon the world. But at the bottom, hope remained. Black-and-white thinking would say she doomed humanity. A balanced view acknowledges both destruction and possibility.

Cassandra’s Curse: Magnifying Negativity

Ever find yourself dwelling only on the negative? Focusing on a single misfortune while ignoring the good?

Cassandra, blessed with the gift of prophecy and cursed to never be believed, saw only impending doom. If she had fixated solely on tragedy, never acknowledging the moments of beauty in life, she would be trapped in negativity. So do we, when we let small misfortunes overshadow everything else.

King Midas’ Touch: Disqualifying the Positive

You succeed, but tell yourself it was luck. You receive a compliment, but dismiss it. You win, but it doesn’t count.

King Midas turned everything to gold but found himself unable to enjoy any of it. When we disqualify the positive, we turn our joys into burdens, never allowing ourselves to embrace them.

Zeus’ Assumptions: Mind Reading

Without evidence, we assume we know what others are thinking. They must hate me. They think I’m stupid.

Zeus often assumed he knew what others thought, leading to mighty conflicts. This is mind reading – when we assume we know others’ thoughts without evidence. Like Zeus, we might stir up trouble based on unfounded assumpt

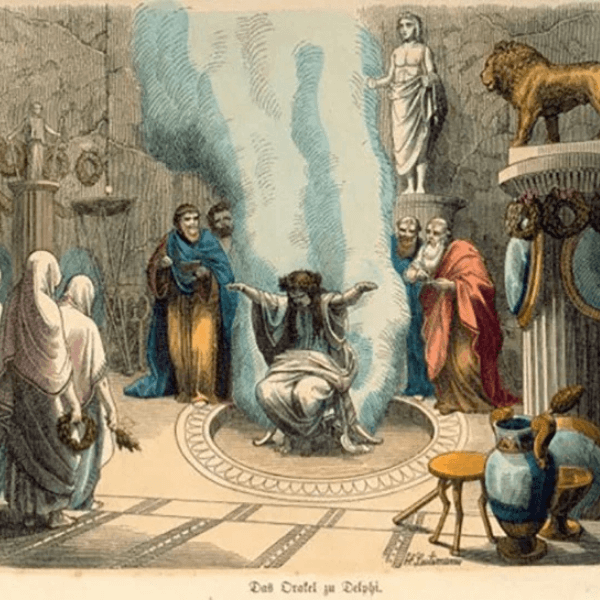

The Oracle of Delphi: Fortune Telling

We predict disaster before it happens. I’m definitely going to fail. This is going to be a disaster.

People visited the Oracle of Delphi to predict their fate. If they believed only in doom and gloom, that’s fortune telling – expecting the worst without any real evidence. It’s like assuming you’ll fail a test before even taking it.

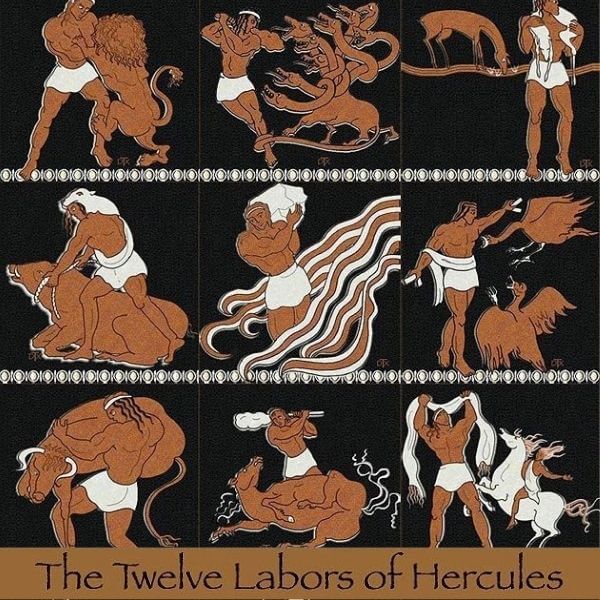

Hercules’ Labors: “Should” and “Must” Thinking

Rigid rules can make life unbearable. I should be perfect. I must never fail.

Hercules believed he had to complete his impossible labors to atone for his past mistakes. He imposed an extreme standard upon himself, believing that unless he succeeded in every task, he would remain unworthy. Much like Hercules, we create unrealistic rules for ourselves, setting expectations that are often impossible to meet. When these self-imposed laws are broken, we feel like failures, when in reality, flexibility and self-compassion would serve us far better.

Hera’s Jealousy: Emotional Reasoning

We feel bad, so we assume reality must be bad. I feel unworthy, so I must be worthless.

Hera often felt jealous and acted on these feelings, thinking they reflected reality. That’s emotional reasoning – letting our feelings dictate our view of situations. Hera’s jealousy didn’t always mean her suspicions were true.

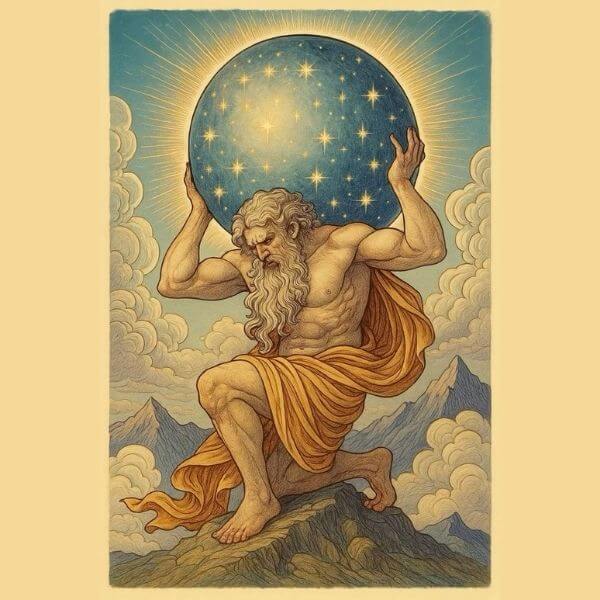

Atlas Carrying the World: Personalization

Everything is our fault. If something goes wrong, we must be to blame.

Atlas was condemned to hold up the sky for eternity, carrying an unbearable burden. He took on a responsibility that was far greater than any one individual could bear. When we engage in personalization, we act as if we, too, are solely responsible for all problems, even those beyond our control. But just as Atlas was eventually relieved of his burden, we must learn to release ourselves from unnecessary guilt.

The Minotaur’s Stigma: Labelling

We assign fixed labels to ourselves or others. I’m a failure. They’re awful people.

The Minotaur, half-man and half-bull, was condemned as a monster from birth and cast into the labyrinth, where he lived in isolation. He was never given a chance to be anything more than his imposed identity. Labeling functions in the same way: it freezes people in rigid categories, ignoring the possibility of change. When we label ourselves or others, we rob ourselves of the chance for growth and transformation.

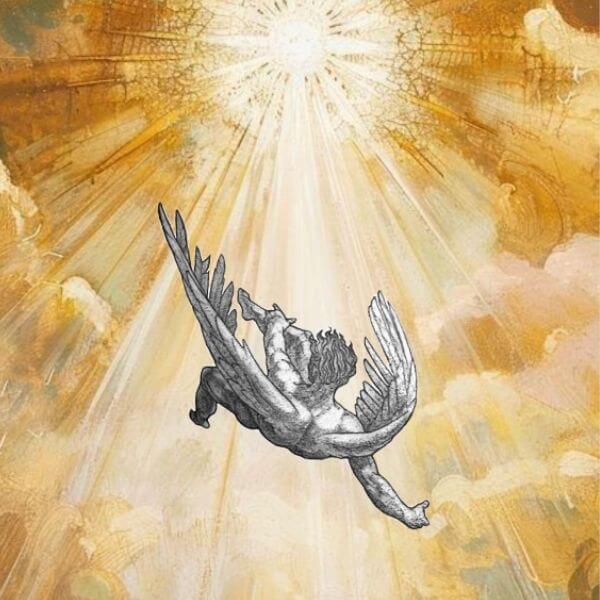

Icarus’ Flight: Catastrophizing

We assume the worst. If I mess up, it’s over. This mistake will ruin my life.

Icarus, warned not to fly too high or too low, panicked and soared too close to the sun. His wax wings melted, and he plummeted to the sea. Catastrophizing is much the same—we envision the absolute worst-case scenario, believing that any mistake will lead to irreversible disaster. Yet, like Icarus, it is not the circumstances that doom us, but our own exaggerated fears. Recognizing that setbacks are part of life—not the end of it—helps us navigate challenges with greater resilience.

Myths as Mental Maps

Mythology has never been just about gods and monsters—it has always been about us. These tales, passed down through centuries, reveal the same cognitive distortions we face today. Achilles’ vulnerability, Pandora’s extremes, Cassandra’s pessimism, and Zeus’ assumptions—these are all mirrors of our own thinking.

The gods may not walk among us, but their wisdom remains. If we listen closely, their stories can still guide us, helping us untangle the errors in our minds and navigate life with greater clarity.

So, the next time you find yourself in a spiral of self-doubt, catastrophizing, or mind reading, ask yourself: Which myth am I living right now? And more importantly—how does the story end?

References:

- Mendoza, M. S. (2021). Nietzsche: Dionysian-Apollonian Lord of the Dance. Eleutheria, 5(2), 258-271.

- O’Flaherty, J. C. (1981). Nietzsche and the Tradition of the Dionysian. In The Young Nietzsche (pp. 193-209). University of North Carolina Press.

- Leeming, D. A. (2014). Apollonian and Dionysian. In Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer.

- Ulanov, A. (1997). Archetypes. In Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer.

- Campbell, J. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library.

- Segal, R. A. (1999). Theorizing about Myth. University of Massachusetts Press.